The need for comprehensive literature searches is less certain in reviews of qualitative studies, and for reviews where a comprehensive identification of studies is difficult to achieve . Different approaches to literature searching and developing the concept of when to stop searching are important areas for further study . The need for thorough and comprehensive literature searches appears as uniform within the eight guidance documents that describe approaches to literature searching in systematic reviews of effectiveness. Reviews of effectiveness , accuracy and prognosis, require thorough and comprehensive literature searches to transparently produce a reliable estimate of intervention effect. The belief that all relevant studies have been 'comprehensively' identified, and that this process has been 'transparently' reported, increases confidence in the estimate of effect and the conclusions that can be drawn . The supporting literature exploring the need for comprehensive literature searches focuses almost exclusively on reviews of intervention effectiveness and meta-analysis.

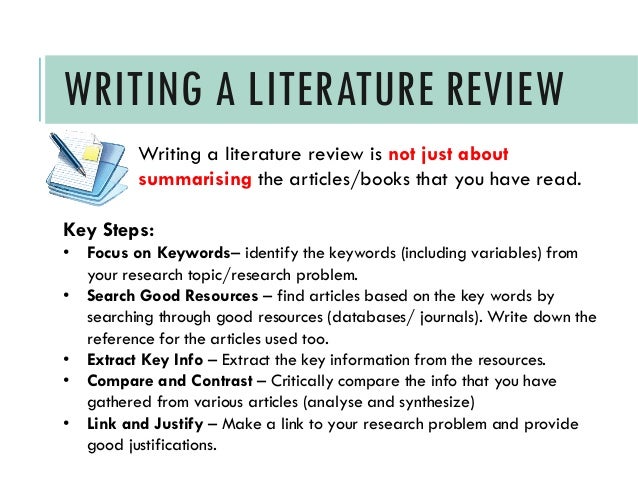

Different 'styles' of review may have different standards however; the alternative, offered by purposive sampling, has been suggested in the specific context of qualitative evidence syntheses . A literature review is an overview of the previously published works on a specific topic. The term can refer to a full scholarly paper or a section of a scholarly work such as a book, or an article. Either way, a literature review is supposed to provide the researcher/author and the audiences with a general image of the existing knowledge on the topic under question. A good literature review can ensure that a proper research question has been asked and a proper theoretical framework and/or research methodology have been chosen. To be precise, a literature review serves to situate the current study within the body of the relevant literature and to provide context for the reader.

In such case, the review usually precedes the methodology and results sections of the work. The average number of bibliographic database searched in systematic reviews has risen in the period 1994– but there remains no consensus on what constitutes an acceptable number of databases searched . This is perhaps because thinking about the number of databases searched is the wrong question, researchers should be focused on which databases were searched and why, and which databases were not searched and why. The discussion should re-orientate to the differential value of sources but researchers need to think about how to report this in studies to allow findings to be generalised. Bethel has proposed 'search summaries', completed by the literature searcher, to record where included studies were identified, whether from database or supplementary search methods . Search summaries document both yield and accuracy of searches, which could prospectively inform resource use and decisions to search or not to search specific databases in topic areas.

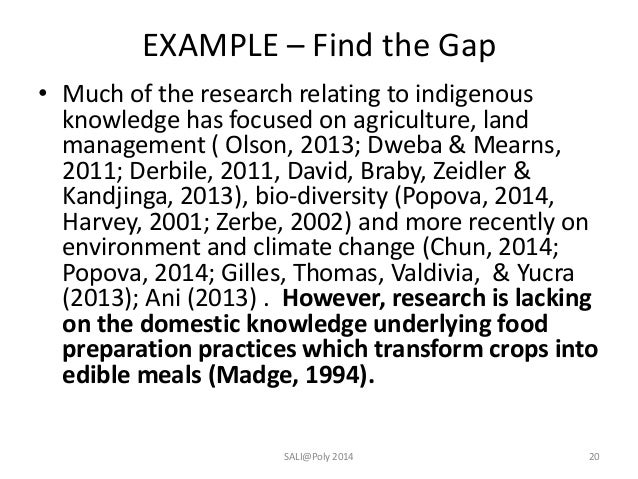

The prospective use of such data presupposes, however, that past searches are a potential predictor of future search performance (i.e. that each topic is to be considered representative and not unique). In offering a body of practice, this data would be of greater practicable use than current studies which are considered as little more than individual case studies . Egger et al., and other study authors, have demonstrated a change in the estimate of intervention effectiveness where relevant studies were excluded from meta-analysis . This would suggest that missing studies in literature searching alters the reliability of effectiveness estimates. Such work is outside the scope of this article, which focuses on literature reviews to inform reports of original medical education research. We define such a literature review as a synthetic review and summary of what is known and unknown regarding the topic of a scholarly body of work, including the current work's place within the existing knowledge.

While this type of literature review may not require the intensive search processes mandated by systematic reviews, it merits a thoughtful and rigorous approach. Defining the key stages in this review helps categorise the scholarship available, and it prioritises areas for development or further study. The supporting studies on preparing for literature searching (key stage three, 'preparation') were, for example, comparatively few, and yet this key stage represents a decisive moment in literature searching for systematic reviews. It is where search strategy structure is determined, search terms are chosen or discarded, and the resources to be searched are selected. Information specialists, librarians and researchers, are well placed to develop these and other areas within the key stages we identify. This review calls for further research to determine the suitability of using the conventional approach.

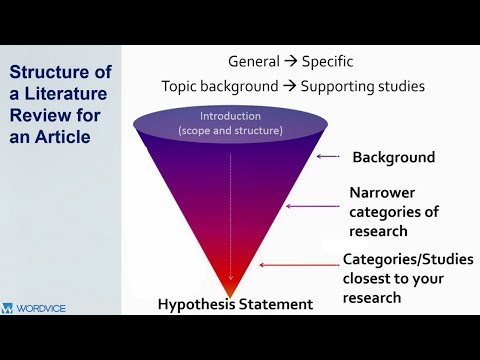

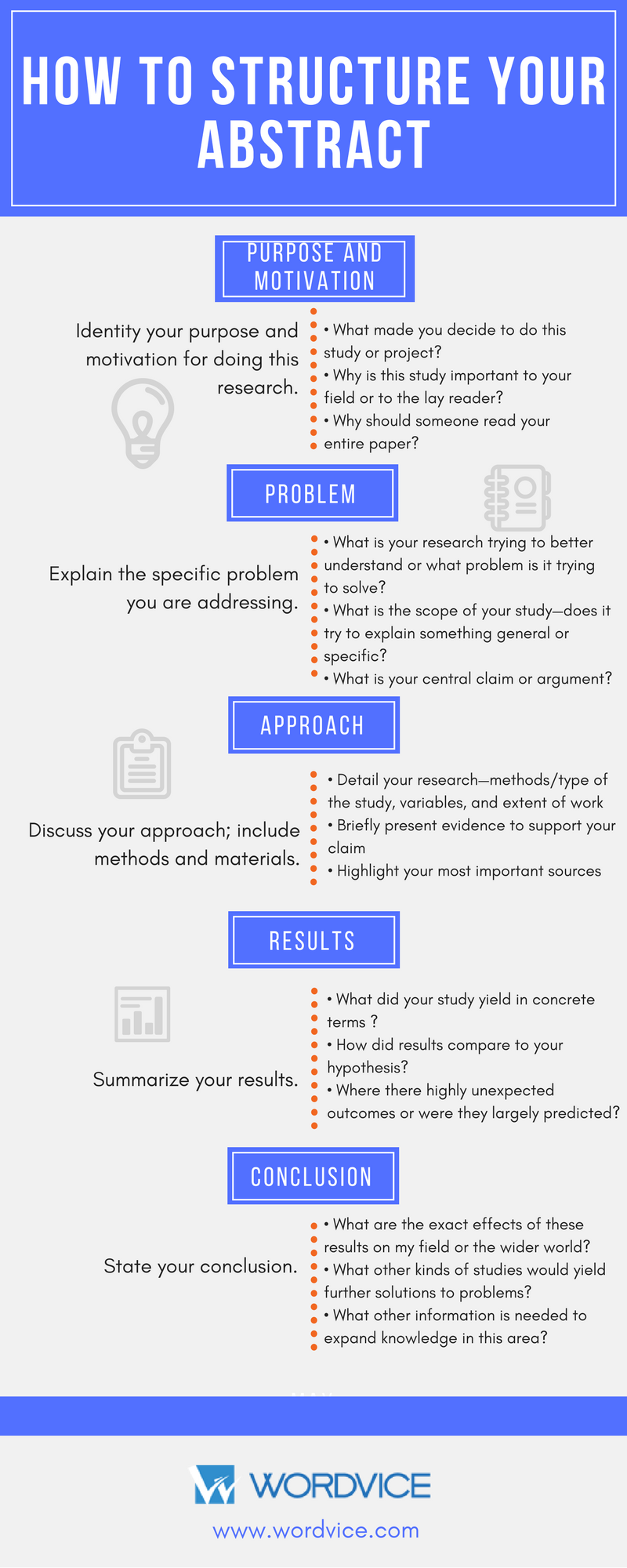

The publication dates of the guidance documents which underpin the conventional approach may raise questions as to whether the process which they each report remains valid for current systematic literature searching. Literature reviews are designed to provide an overview of sources you have explored while researching a particular topic and to demonstrate to your readers how your research fits within a larger field of study. Because you need to discuss a wide range of sources in a literature review, you may find it difficult to narrow your focus for an effective critique and understanding of research on the topic. Indeed, you may need to consider theoretical frameworks, methodology, and a variety of data sources or evidence alongside the findings and conclusions put forth by the authors of the articles and books that inform your review. It is important to consider the purpose of your literature review to ensure you ask appropriate questions of your topic.

Reporting of literature searching is a key area in systematic reviews since it sets out clearly what was done and how the conclusions of the review can be believed . Despite strong endorsement in the guidance documents, specifically supported in PRISMA guidance, and other related reporting standards too , authors still highlight the prevalence of poor standards of literature search reporting . Atkinson et al. have also analysed reporting standards for literature searching, summarising recommendations and gaps for reporting search strategies .

The purpose of thorough and comprehensive literature searches is to avoid missing key studies and to minimize bias since a systematic review based only on published studies may have an exaggerated effect size . Felson sets out potential biases that could affect the estimate of effect in a meta-analysis and Tricco et al. summarize the evidence concerning bias and confounding in systematic reviews . Egger et al. point to non-publication of studies, publication bias, language bias and MEDLINE bias, as key biases . Comprehensive searches are not the sole factor to mitigate these biases but their contribution is thought to be significant . Fehrmann suggests that 'the search process being described in detail' and that, where standard comprehensive search techniques have been applied, increases confidence in the search results . Over the past few years, numerous studies and research articles have been published in the medical literature review domain.

The topics covered by these researches included medical information retrieval, disease statistics, drug analysis, and many other fields and application domains. In this paper, we employ various text mining and data analysis techniques in an attempt to discover trending topics and topic concordance in the healthcare literature and data mining field. This analysis focuses on healthcare literature and bibliometric data and word association rules applied to 1945 research articles that had been published between the years 2006 and 2019. Our aim in this context is to assist saving time and effort required for manually summarizing large-scale amounts of information in such a broad and multidisciplinary domain. To carry out this task, we employ topic modeling techniques through the utilization of Latent Dirichlet Allocation , in addition to various document and word embedding and clustering approaches.

Findings reveal that since 2010 the interest in the healthcare big data analysis has increased significantly, as demonstrated by the five most commonly used topics in this domain. A systematic literature review identifies, selects and critically appraises research in order to answer a clearly formulated question (Dewey, A. & Drahota, A. 2016). The systematic review should follow a clearly defined protocol or plan where the criteria is clearly stated before the review is conducted. It is a comprehensive, transparent search conducted over multiple databases and grey literature that can be replicated and reproduced by other researchers. It involves planning a well thought out search strategy which has a specific focus or answers a defined question. The review identifies the type of information searched, critiqued and reported within known timeframes.

The search terms, search strategies and limits all need to be included in the review. When to database search is another question posed in the literature. Beyer et al. report that databases can be prioritised for literature searching which, whilst not addressing the question of which databases to search, may at least bring clarity as to which databases to search first . Paradoxically, this links to studies that suggest PubMed should be searched in addition to MEDLINE since this improves the currency of systematic reviews . Cooper et al. have tested the idea of database searching not as a primary search method but as a supplementary search method in order to manage the volume of studies identified for an environmental effectiveness systematic review. Their case study compared the effectiveness of database searching versus a protocol using supplementary search methods and found that the latter identified more relevant studies for review than searching bibliographic databases .

From the guidance, we determined eight key stages that relate specifically to literature searching in systematic reviews. Table 2 reports the areas of common agreement and it demonstrates that the language used to describe key stages and processes varies significantly between guidance documents. Eight key stages to the process of literature searching in systematic reviews were identified. These key stages are consistently reported in the nine guidance documents, suggesting consensus on the key stages of literature searching, and therefore the process of literature searching as a whole, in systematic reviews.

Further research to determine the suitability of using the same process of literature searching for all types of systematic review is indicated. The findings reported above reveal eight key stages in the process of literature searching for systematic reviews. These key stages are consistently reported in the nine guidance documents which suggests consensus on the key stages of literature searching, and therefore the process of literature searching as a whole, in systematic reviews. What is not clear is the extent to which the guidance documents inter-relate or provide guidance uniquely.

The Cochrane Handbook, first published in 1994, is notably a key source of reference in guidance and systematic reviews beyond Cochrane reviews. Since we cannot be clear, we raise this as a potential limitation of this literature review. On our initial review of a sample of North American, and other, guidance documents , however, we do not consider that the inclusion of these further handbooks would alter significantly the findings of this literature review. Table 2 also summaries the process of literature searching which follows bibliographic database searching. As Table 2 sets out, guidance that supplementary literature search methods should be used in systematic reviews recurs across documents, but the order in which these methods are used, and the extent to which they are used, varies.

We noted inconsistency in the labelling of supplementary search methods between guidance documents. Eight documents provided guidance on who should undertake literature searching in systematic reviews . The guidance affirms that people with relevant expertise of literature searching should 'ideally' be included within the review team .

Information specialists , librarians or trial search co-ordinators are indicated as appropriate researchers in six guidance documents . Literature refers to a collection of published information/materials on a particular area of research or topic, such as books and journal articles of academic value. However, your literature review does not need to be inclusive of every article and book that has been written on your topic because that will be too broad. Rather, it should include the key sources highlighting the main debates, trends and gaps in your specific research area. The literature review is a written overview of major writings and other sources on a selected topic.

Sources covered in the review may include scholarly journal articles, books, government reports, Web sites, etc. The literature review provides a description, summary and evaluation of each source. It is usually presented as a distinct section of a graduate thesis or dissertation. Once you have evaluated the research of others, you need to consider how to integrate ideas from other scholars with your ideas and research project. You will also need to show your readers which research is relevant to understanding your project and explain how you position your work in relationship to what has come before your project.

In order to do this, it may be helpful to think about the nature of your research project. For example, your research project may focus on extending existing research by applying it in a new context. Or you may be questioning the findings of existing research, or you may be pulling together two or more previously unconnected threads of research. Or your project may be bringing a new theoretical lens or interpretation to existing questions.

The focus of your research project will determine the kind of material you need to include in your literature review. How the reporting of the literature searching process corresponds to critical appraisal tools is an area for further research. In the survey undertaken by Radar et al. , 86% of survey respondents (153/178) identified a need for further guidance on what aspects of the literature search process to report . The PRISMA statement offers a brief summary of what to report but little practical guidance on how to report it . We were able to identify consensus across the guidance on literature searching for systematic reviews suggesting a shared implicit model within the information retrieval community. Whilst the structure of the guidance varies between documents, the same key stages are reported, even where the core focus of each document is different.

We were able to identify specific areas of unique guidance, where a document reported guidance not summarised in other documents, together with areas of consensus across guidance. Once a list of key guidance documents was determined, it was checked by six senior information professionals based in the UK for relevance to current literature searching in systematic reviews. To facilitate writing a literature review, journals are increasingly providing helpful features to guide authors. Additionally, many institutions have writing centers that provide web-based materials on writing a literature review, and some even have writing coaches. The purpose of sources and references is to provide valuable information. Use relevant keywords, and find credible academic references that add value to your research paper and strengthen your position.

Read and evaluate them to understand assumptions made by other researchers, in addition to the methodologies used. Highlight the names of notable experts in your field and list all conflicting opinions in your literature review. Finding models of other literature reviews is essential as it helps you see how others handled similar tasks.

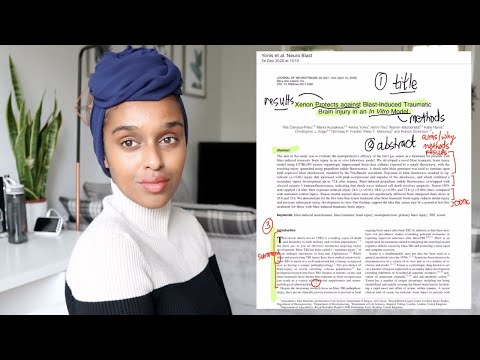

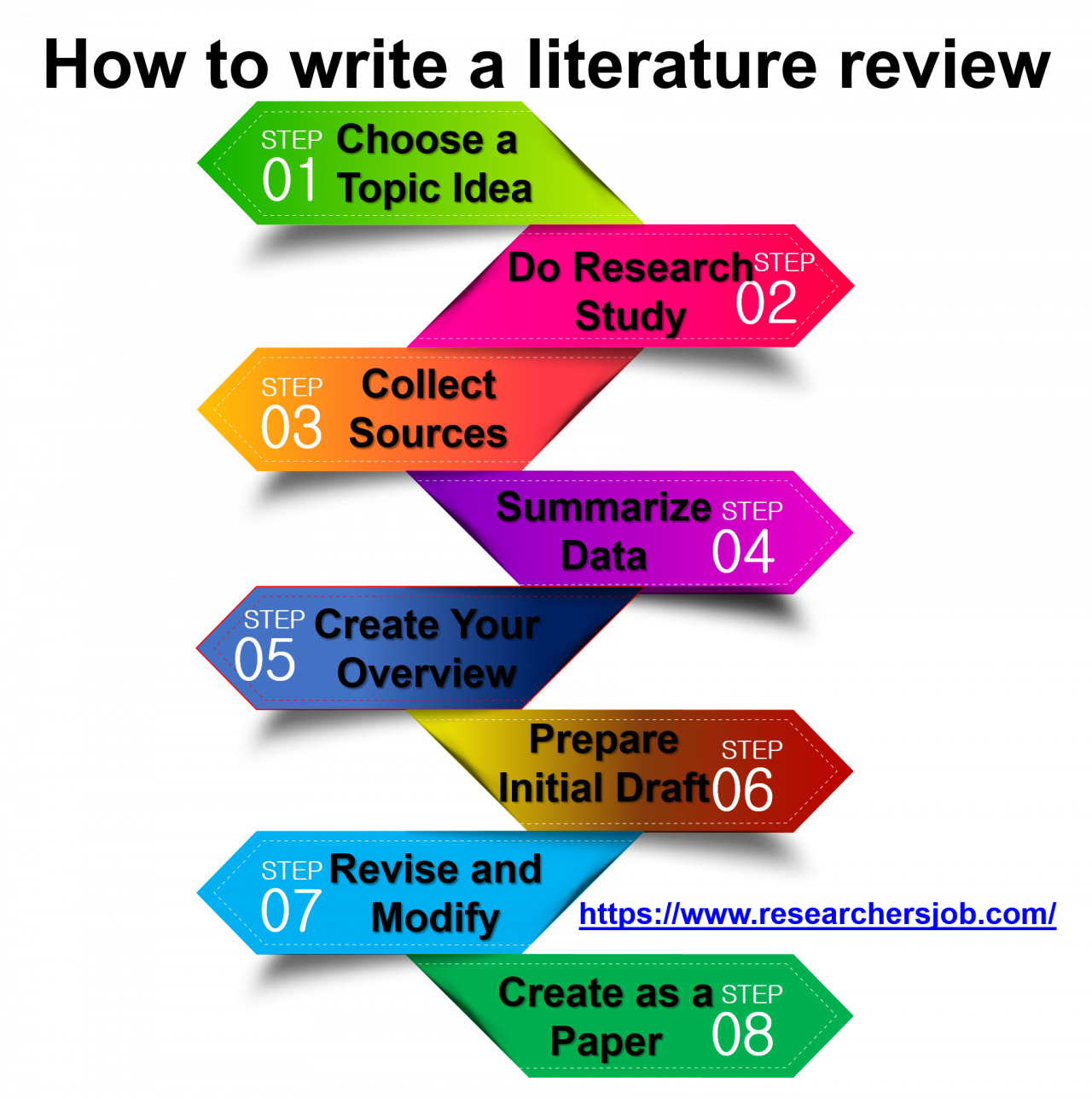

Many researchers struggle when it comes to writing literature review for their research paper. A literature review is a comprehensive overview of all the knowledge available on a specific topic till date. Literature review is one of the pillars on which your research idea stands since it provides context, relevance, and background to the research problem you are exploring. While I present steps one and two as sequential, in reality, it's more of a back and forth tango – you'll read a little, then have an idea, spot a new citation, or a new potential variable, and then go back to searching for articles. This is perfectly natural – through the reading process, your thoughts will develop, new avenues might crop up, directional adjustments might arise. This is, after all, one of the main purposes of the literature review process (i.e. to familiarise yourself with the current state of research in your field).

As a second step on how to write a literature review, you need to dig deeper into search engines to discover what has already been published in your chosen domain. Make sure you thoroughly go through appropriate reference sources like books, reports, journal articles, government docs, and web-based resources. This literature review would appear to demonstrate the existence of a shared model of the literature searching process in systematic reviews.

We call this model 'the conventional approach', since it appears to be common convention in nine different guidance documents. The guidance documents summarise 'how to' search bibliographic databases in detail and this guidance is further contextualised above in terms of developing the search strategy. The host of the database (e.g. OVID or ProQuest) has been shown to alter the search returns offered. Younger and Boddy report differing search returns from the same database but where the 'host' was different . Two key tasks were perceptible in preparing for a literature searching .

One way of developing such a conceptual model is by formally examining the implicit "programme theory" as embodied in key methodological texts. The aim of this review is therefore to determine if a shared model of the literature searching process in systematic reviews can be detected across guidance documents and, if so, how this process is reported and supported. The relevant sections within each guidance document were then read and re-read, with the aim of determining key methodological stages. This data was reviewed to identify agreements and areas of unique guidance between guidance documents.

Consensus across multiple guidance documents was used to inform selection of 'key stages' in the process of literature searching. Systematic literature searching is recognised as a critical component of the systematic review process. A literature review is a summary of the published work in a field of study. This can be a section of a larger paper or article, or can be the focus of an entire paper. Literature reviews show that you have examined the breadth of knowledge and can justify your thesis or research questions.

They are also valuable tools for other researchers who need to find a summary of that field of knowledge. The purpose is to offer an overview of significant literature published on a topic. Literature reviews provide you with a handy guide to a particular topic. If you have limited time to conduct research, literature reviews can give you an overview or act as a stepping stone. For professionals, they are useful reports that keep them up to date with what is current in the field. For scholars, the depth and breadth of the literature review emphasizes the credibility of the writer in his or her field.

Literature reviews also provide a solid background for a research paper's investigation. Comprehensive knowledge of the literature of the field is essential to most research papers. Some disciplines require that you use information that is as current as possible. This is particularly true in disciplines in medicine and the sciences where research conducted becomes obsolete very quickly as new discoveries are made.

However, when writing a review in the social sciences, a survey of the history of the literature may be required. In other words, a complete understanding the research problem requires you to deliberately examine how knowledge and perspectives have changed over time. Sort through other current bibliographies or literature reviews in the field to get a sense of what your discipline expects. You can also use this method to explore what is considered by scholars to be a "hot topic" and what is not. In addition, this type of literature review is usually much longer than the literature review introducing a study. At the end of the review is a conclusion that once again explicitly ties all of these works together to show how this analysis is itself a contribution to the literature.

While it is not necessary to include the terms "Literature Review" or "Review of the Literature" in the title, many literature reviews do indicate the type of article in their title. Whether or not that is necessary or appropriate can also depend on the specific author instructions of the target journal. Have a look at this article for more input on how to compile a stand-alone review article that is insightful and helpful for other researchers in your field.